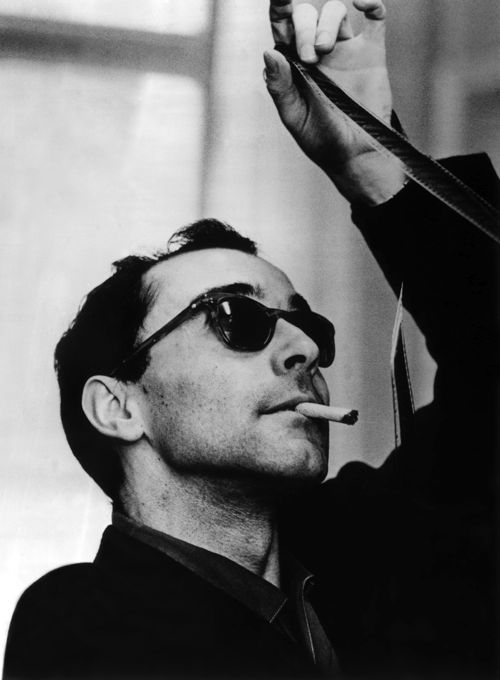

In 1960, Jean Luc Godard burst onto the cinema landscape with his groundbreaking debut film Breathless, a huge critical and commercial success that ushered in the influential French New Wave momement. One can make the argument that from his debut film onwards, Godard's 1960s work defined the entire turbulent decade. Indeed, Godard has an astonishing 12 films from the 1960s in the prestigious Criterion Collection, which is perhaps the most respected DVD/Blu Ray distributor of classic and important contemporary films.

As the 1960s came to an end, Godard’s work became more experimental and politically radical. Godard didn’t want to only entertain audiences; instead, he wanted to engage viewers in an active and cerebral manner. As events such as the Vietnam War and the 1968 student protest movements dominated the social and political climate, Godard felt that cinema had to actively address these issues. This led Godard to start making politically radical films such as Weekend, La Chinoise, and a series of works known collectively as the Dziga Vertov Group films.

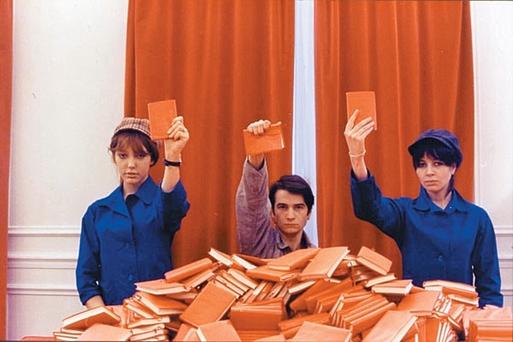

La Chinoise is Godard’s most politically incisive work. With its examination of Marxism and the student protest movement, La Chinoise is Godard’s ultimate manifesto on the politics of the 1960s. It takes the same vibrant color palette of his less political films, such as Pierrot le fou and Made in U.S.A., and places it within a story of student revolutionaries in France during the late 1960s. Most of La Chinoise takes place in a single apartment shared by a group of young students who are deeply dissatisfied with the government.

La Chinoise translates to the Chinese, alluding to the fascination that 1960s student intellectuals had with the ideas of Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution in China. These students were deeply influenced by Mao’s leadership role in the revolt of the proletariat class against the bourgeoisie. Throughout La Chinoise, we see the students reciting from Mao’s Little Black Book, and even dressing in the traditional dark blue clothing of the Chinese peasant revolutionaries.

Another important thinker that the students are influenced by is Karl Marx, who espoused a similar critique about the dialectical struggle between the proletariat and the elite classes. However, while the students spend their days studying the works of Marx and Mao, Godard ultimately views their actions with disdain and skepticism. For Godard, the students are hypocrites because while they talk about oppression and exploitation, they never actually leave their apartment to engage with the outside population that they claim to want to help.

Instead, as Godard reveals, the students spend their days isolated from the wider society, entertaining themselves with theatrical games. In one scene, a student stands in front of the other students, reading aloud from the works of Marx. The seated students holler and yell at the standing student, as if he was an actor performing for them. Godard emphasizes this theatrical aspect of the scene further by panning back and forth from a distance between the standing and seated students, as if the viewer was yet another spectator of this grand theatrical production.

In another scene, one of the students states directly that the Vietnam War is a performance made up of different actors, with the United States, the Soviet Union, and Vietnam as the three main players. For these students, politics is just a form of distraction, or a way to entertain themselves without having to face the real world.

Thus, Godard ultimately views the students’ activities as being meaningless. For Godard, it is futile to endlessly discuss political issues without taking any action. And when the students do finally decide to take action, the result is equally misguided, as they ultimately resort to violence.

La Chinoise is a biting indictment of the deep gap which can exist between action and thought. The students in La Chinoise espouse revolutionary thoughts, but their actions do not reflect this. They ultimately do not succeed because in the end, they are members of the same class that they are trying to overthrow—the elite, bourgeois class. Marx argued that a revolution must be carried out from the bottom up, as happened during the Cultural Revolution in China, not from the top up, as the students in La Chinoise are attempting to do.

For Godard, bourgeois cinema seeks only to entertain, just as the students in La Chinoise seek to entertain themselves with theatrical games. Instead, from the late 1960s and throughout the rest of his career, Godard sought to create a form of cinema that actively engages audiences, and forces them to view films in a new light. Perhaps this is why many have chosen to ignore Godard’s wide output of great work after the 1960s, and to focus instead only on his earlier, more accessible films. La Chinoise was Godard’s first film to completely divorce itself from the bounds of traditional narrative filmmaking, and to point cinema in a new, innovative direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment