During the 1960s, many visions for a Utopian future existed—one which could only be achieved through technological innovations. The common perception of the 1960s was that science was boundless in terms of its ability to advance human society. Science allowed us to reach beyond the limits of Earth; on July 20, 1969, the United States astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human on the moon. This achievement occurred in the larger context of the Cold War, during which the U.S. and Russia fought each other to gain technological global dominance. As a result of this rivalry, the United States’ striving for dominance in the field of science was fertile grounds for creative expression by many 1960s artists.

Stanley Kubrick's 2001 was the most significant film from the 1960s which reflected this glorification of science. Although it presented a Utopian future of the United States as colonizing and exploring space freely, 2001 also revealed the limits and the dangers of technology. In a world of rapid technological changes, the self-destructive side of science is a frightening reality.

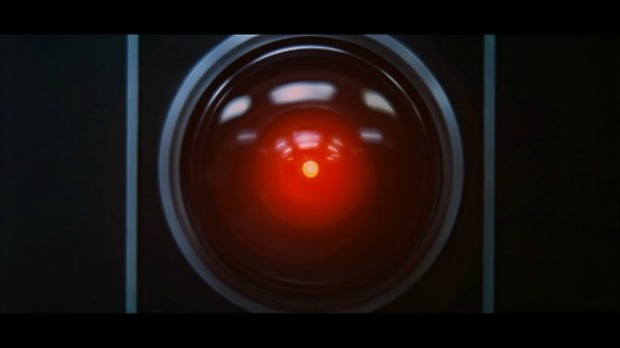

Kubrick’s 2001 portrays humans in the process of creating wondrous technological advancements, such as building a space station and landing on distant planets. In the film, the United States has sent a group of scientists, including the lead character of David, to explore the solar system. The lives of these scientists are in the hands of HAL, a super computer which is a highly advanced form of artificial intelligence.

At first, HAL cooperates with David and his crew, carefully monitoring those who are in suspended animation, and even playing chess with David when he is bored. At this point in the film, man and technology live in harmony, which each side benefiting from the other; Hal keeps David and the other scientists alive and functioning safely in the hostile atmosphere of outer space, and David keeps HAL company by talking with him.

This state of peaceful co-existence between man and technology is what scientists in the 1960s wanted to maintain. Scientists were aware of the darker side of technological development, such as the destructive power of nuclear weapons, but they consciously chose to ignore the dangers of science in order to help the United States gain global dominance over Russia.

Kubrick realized that at a certain point, the harmony between man and science could reach a breaking point—eventually, HAL starts to make mistakes, and David and his crew debate over whether or not to turn HAL off. This leads to HAL becoming more and more malevolent, as its decisions start to threaten the safety of David and his crew.

The creators of technology ultimately have control over how scientific innovations are used, and if the creators are inherently destructive, then their creation will also be destructive. The irony of 2001 is that despite all the technological advancements that humans have made, they have not been able to evolve beyond their inherent desire to destroy themselves.

2001 opens with the dawn of man, which is depicted as a dark era when the first humans, in the form of apes, lived in fear of the dark, and constantly fight and kill each other over territory. The major technological advancement which occurs with these first humans is the discovery of the bone, which is ultimately used as a tool to kill other apes. The bone itself is discovered after the apes kill another species of animal; thus the first scientific discovery could only be created through murder.

In one of the most celebrated cuts in all of cinematic history, an ape throws a bone into the sky, and Kubrick cuts from the upward motion of the bone to an image of a nuclear device floating in space. This single cut reveals how little humans have evolved, despite all of our amazing technological advancements. Kubrick is saying that if we cannot evolve beyond our nature to kill each other, then we are doomed to ultimately destroy ourselves.

However, Kubrick’s 2001 is not ultimately a pessimistic portrait of humankind. Rather, it is a warning against the human race’s natural inclination to recede to its baser nature.

Friedrich Nietzsche said, “All beings so far have created something beyond themselves; and do you want to be the ebb of this great flood and even go back to the beasts rather than overcome man?” Man in his basest nature is an ape, whose natural instincts are to destroy life and conquer land.

However, it takes great effort to overcome these primal desires, and to ultimately become what Nietzsche referred to as a “superman.” This concept of the superman has been greatly misunderstood by those in power, and has been used to justify war and destruction, as in the case of Hitler’s Nazi Germany. In order to become a real superman, a cleansing of what Nietzsche refers to as the polluted nature of mankind is necessary.

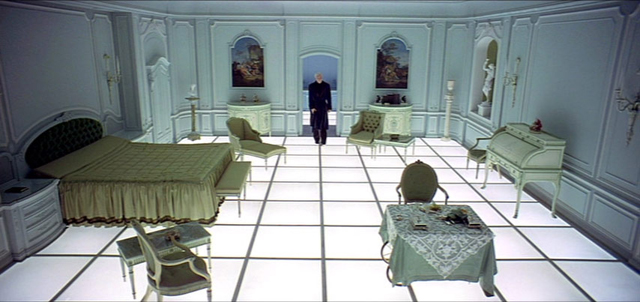

This cleansing is revealed in 2001 by the increasingly clean environments which the humans reside in throughout the film. The first environment we see is the jagged and soil-filled environment of the apes. This dirtier, more natural environment is replaced by the geometrically precise and clean environments of the spaceships. The last environment is that of the elegant and clinically clean rooms which David lives in before he dies.

Like the monoliths strategically placed in the film, an increasingly cleaner environment accompanies each stage of human evolution in 2001. The final stage of evolution in 2001 is the rebirth of mankind into a higher consciousness—one based upon an alignment of the planets with the last monolith. This final monolith serves as both a warning and a symbol of hope for the human race.

2001 is both the most pessimistic warning against the destruction of humankind, and the most optimistic portrayal of our ability to evolve into a higher state of consciousness.