It's interesting that ever since the Academy of Motion Picturs Art and Sciences anounced their new, more inclusive rules for eligibility for the Best Picture category, a culture war has developed between those who support the new rules as a step forward in opporutnities for minorities, and those who view the rules as somehow being a form of creative censorship and authoritarianism. Ironically, many of those in this latter camp are the same free-thinking individuals who supported the Black Lives Matter movement and were vocal in their support for police reform against brutality towards African-Americans. Now, when the Academy is doing its part to provide more equal opportunities for underrepresented communities in the industry, these formerly progressive advocates for equality are suddenly outraged and accusing the Academy of "stifling creativity."

Before we get into why so many of these individuals are so angry let's examine closely what exactly the new Academy rules are. In an effort to provide more opportunities for minorities both in front of and behind the camera in key leadership roles, the Academy implemented new rules that, starting in 2024, in order for a film to qualify for a Best Picture nomination, it must meet two out of these four standards (A through D):

Standard A (On-Screen Representation, Themes, and Narratives)-- To qualify, the film must meet one of these three criteria:

A1: At least one of the actors, either in a lead or a supporting role, must belong to an ethnic minority grouop.

A2: At least 30% of all actors in secondary and more minor roles are from at least two of the following underrepresented groups: women, racial or ethnic group, LGBTQ+, people with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing.

A3: The main storyline(s), theme or narrative of the film is centered on an underrpresented group(s)--women, racial or ethnic grouop, LGBTQ+, people with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Standard B (Creative Leadership and Project Team)- To qualify, the film must meet one of these three criteria below:

B1: At least two of the following creative leadership positions and department heads (Casting Director, Cinematographer, Composer, Costume Designer, Director, Editor, Hairstylist, Makeup Artist, Produer, Production Designer, Set Decorator, Sound, VFX Supervisor, Writer) are from the following underrpresented groups:

• Women

• Racial or ethnic group

• LGBTQ+

• People with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing

At least one of those positions must belong to an ethnic minority group.

B2: At least six other crew/team and technical positions are from an underrpresented racial or ethnic group.

B3: At least 30% of the film's crew is from the following underrepresented groups:

• Women

• Racial or ethnic group

• LGBTQ+

• People with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing

And, to summarize the remaining standards, for Standard C, a film must have paid apprenticeships, internships, and training opporunities for underrpresented groups, and for Standard D, a film should have multiple in-house senior executives from an underrepresented group on their marketing, publicity, and/or distribution teams.

The key to understanding these rules are that for a film to be eligible for Best Picture, the film must only meet two out of four of the standards, and within each standard, the film would have to meet only one of the three required rules. Many of those who are opposed to the rules change state that it is somehow a form of censorhip which will stifle the creativity of the filmmakers, because it would require them to insert a minority actor/character into the film even if that character is not part of the original storyline. However, a film could qualify even if it featured an all-White cast and all-White themed storyline as long as some of the paid interns/trainees and in-house senior executives are minorities (that would qualify the film under standards C and D).

This pretty much destroys the argument by those who are against these rules as somehow stifling "creative freedom," as nothing in the actual film's storyline or character descriptions has changed, as long as the film production has employed some minority key crew members or interns/trainees.

In fact, by giving key crew positions to minorities and/or underrepresented groups, a film is opening up opporutnities for those who normally would be passed over for these positions, and this in the end would benefit the film production as a whole as it would offer a diversity of voices in the creative decision making processes of the film. These new rules are not some sort of a draconian Hays Code form of censorship dictating to filmmakers what they can or cannot film; rather, they are guidelines to provide more opportunities for ethnic groups and underrepresented communities that have traditionally been ignored on film sets.

Even if a film wanted to try to qualify under standards A and B, all the filmmakers would have to do is have at least one actor in either a lead or supporting role who was a minority or member of an underrepresented group, and hire a key leadership crew member from the same categories. Would having one Asian-American actor on set and one African-American director on set somehow ruin the creative vision of a film that otherwise was a majority White production? Those who are arguing against these new rules somehow seem to feel threatened by the presence of having two non-White people in key roles on set, and this is very troubling. It's as if those who are against implementing these new rules somehow think the African-American director and Asian-American actor would somehow conspire together to sabotage the film.

Some have even argued that by requiring a certain number of minorities on a film set, it will prevent other more qualified people from being hired solely based on their skillset. By following this line of reasoning, it implies that by introducing minorities into potential consideration for film jobs, the overall skill level for the film set will not be as consistent because the minorities are not as skilled or qualified as the non-minority film crew members. Thus, historically, Hollywood has hired White actors to portray minority characters because they were considered more talented than their minority counterparts.

This thinking is what could have led Disney to decide to hire only White crew members in all the major leadership positions, from director, to writer, to cinematographer, on their Chinese set and themed film Mulan. It was Disney's intention to create an "authentic" portayal of Chinese culture, and they didn't think it would be beneficial to hire Chinese lead crew members who had intimate knowledge of their own culture to help them in their efforts? Instead, it is glaring that not a single key consultant on the Mulan film was Chinese; my only thought was that xenophobia played a role and they didn't want to give Chinese people control over the telling of their own stories.

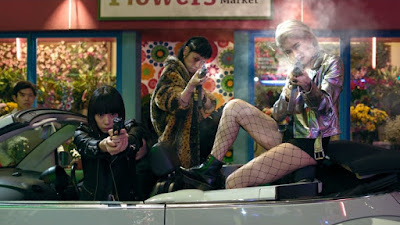

On the other hand, the Disney film Black Panter (albeit it was more of a Marvel film) was the opposite of the Mulan situation in the sense that not only were all the lead actors African-American, but the director and many of the lead crew positions were also African-Americans and minorities. This resulted in a film that creatively touched on many aspects of Black culture to tell a unique and compelling story about the African-American experience in the form of a super hero film. Mulan could have turned out the same way, but instead we got a White-washed portrait of Chinese culture that couldn't even resonate with audiences in China itself.

The history of Hollywood is rife with examples of non-representation of minority cultures, from casting Al Jolson, a white lead actor in blackface, to play an African-American character in the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, to casting Rex Harrison, a British actor, to play the Asian lead character in the 1946 film Anna and the King of Siam. Even behind the camera, Hollywood has traditionally hired White creative leads to tell the story of non-minority cultures, as exemplified in misfires such as Memoirs of a Geisha, which also cluelessly cast Chinese actors to play Japanese characters.

So, the new Academy rules are smartly addressing these issues by encouraging filmmakers to employ more minorities in key leadership positions both behind and in front of the camera to tell more accurate stories about their own cultures. Again, even if filmmakers were telling an all-White themed story, all they would have to do is employ key crew positions with minorities, which would only benefit the film in the end by opening up opportunities for underrepresented communities, and bring diverse voices into the mix.

The same seemingly progressive individuals who support BLM and are agaisnt police brutatlity are suddenly up in arms over the new Academy rules for inclusivity in the industry, but as I explained above, these rules are not some new form of creative censorship. If you read the rules carefully, you can clearly see that they are framed to simply allow more opportunities for minorities and underrepresented groups to contribute to the making of a film.

The rules do not dictate that you have to arbitraly include a minority character into your film; instead, you just have to open up your mind and allow those who have traditionally been ignored some decision making input on your film set, either behind the camera or in front of it. If you view the rules this way, you'll see that the new rules are not about exluding your creative freedom and power, instead it's about including those who want their voices to finally be heard into the filmmaking process.