Asian Ovation

A blog from me, Jeffrey Wang, about Asian film and culture, as well as discussions of films from throughout the world. I am an Asian-American filmmaker and writer. Please check out my books for sale at Amazon at this link: CLICK HERE

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

FILM REVIEW: MINARI

Tuesday, April 6, 2021

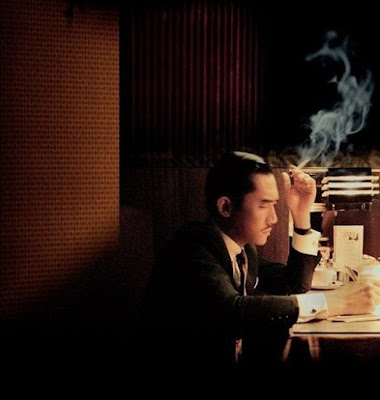

FILM REVIEW: 2046

In Buddhism, there is a common saying that attachment leads to suffering, and one must learn to let go of all material and emotional connections in order to gain peace. Throughout his films, Wong Kar-wai explores this universal need to connect emotionally and at times carnally with another person, and the inability for us to ever truly become satisfied as a result of these amorous pursuits. From Maggie Cheung's thwarted love for Leslie Cheung in Days of Being Wild, through the now almost iconic unconsummated relationship of Faye Wong and Tony Leung in Chungking Express, and up to the melancholic yearnings of Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung again in the swooningly atmospheric In the Mood for Love, Wong Kar-wai has become the cinematic master of missed connections. While he took a detour into the wu xia genre with his impressionistic martial arts films Ashes of Time and The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai has explored characters haunted by lost loves throughout his filmography. After making seven increasingly accomplished films, Wong reached an aesthetic and emotional peak with 2046 (2004), a masterfully rendered, dream-like meditation on romantic longing.

2046 is a direct sequel to In the Mood for Love, as it explores the troubled life of the writer Chow Mo-wan (played by Wong Kar-wai's regular leading man Tony Leung) after he leaves Su Li-shen (Maggie Cheung), a married woman that he fell deeply in love with. To compensate for his grief, Chow has a series of amorous encounters with various women, most notably with Su Li-shen (Gong Li), Wang Jing-wen (Faye Wong), and Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi), some of whom turn up as characters in his own stories. Freely flowing back and forth through time, and also into the narratives of Chow's own writing, 2046 is an impressionistic portrait of unfulfilled desire.

Wong's films are very much a visual experience, with astonishing cinematography from the brilliant Christopher Doyle, and 2046, along with In the Mood for Love, represent the apotheosis of Wong's and Doyle's collaboration. 2046 is filled with images of beautiful decay, as characters are framed against decrepit, worn-out buildings bathed in luxurious colors. These dilapidated backdrops represent the fading memories of Wong's characters, who are mourning for a dying past that can never be truly reclaimed. Like Marcel Proust's Remembrance of Things Past, Wong's films, and in particular 2046, are about protagonists who spend their days haunted by the many lives and loves they destroyed.

2046 begins and ends with the image of a large tunnel that is framed by an elegant shell-like structure, against a futuristic backdrop. With this baroque tunnel, Wong is collapsing all time, from the past, present, and future, into a single image. This tunnel recalls the hole that Chow whispered his secret love for Su into from In the Mood for Love, while it also represents the present day of Chow as he is writing about the tunnel in a science fiction story set in the future. For Wong, the various time periods that he references throughout 2046, from the past affair of Su and Chow explored in In the Mood for Love, to the current sometimes cruel relationships Chow has with a series of women in the present day of 2046, along with the imaginary loves of Chow's fictional characters in his story set in the future, are tied together by an unfulfilled yearning to connect deeply with another person who can never fully reciprocate the same feelings.

The significance of 2046 as a number is that it is the year mainland China will officially reclaim Hong Kong. No one can yet predict how this will affect Hong Kong once it rejoins China completely, but it is this sense of the past being reclaimed by an unknown future that permeates all of Wong's films. 2046 is both the room number that Chow lives in, and also a destination in his fictional story where characters go to reclaim lost loves. In this sense, Wong uses the number 2046 to symbolize his characters' constant yearning to reclaim a more romanticized past that they can never truly recover, just as Hong Kong is in a temporary sovereign state of being which will disappear in the year 2046. Once the year 2046 occurs, Hong Kong will have to let go of its British influenced colonial past and enter into an unknown future; this is why Chow notes that when the characters in his story reach 2046, they can never return again.

Indeed, throughout all his films, the handover of Hong Kong to China in the year 2046 is referenced repeatedly with the motif of time as being fleeting and elusive. The concept of an expiration date occurs in Chungking Express, with He Qiwu (Takeshi Kaneshiro) obsessing about finding a can of pineapples with the same expiration date as the date his ex-girlfriend broke up with him. In Fallen Angels, Takeshi Kaneshiro plays another character who muses about if relationships have expiration dates. There's also the symbolism of clocks and time periods in Wong's films, most notably in Days of Being Wild, as Maggie Cheung's character Li-zhen mourns over the one minute period given to her by Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), which delineates the time frame for their relationship's length. In As Tears Go By, In the Mood for Love, and Happy Together, characters are unable to fulfill their longing to be together due to temporal disconnects and lapses. Wong's characters are both enamored by time as a means to consummate a relationship, and mournful over its inherent nature of bringing things to an end.

If we all had the ability to go back in time to either fix or reclaim a lost love, can we ever truly be the same person again? Our entire lives would be changed, and we essentially would be entering into a parallel track of our existence, one predicated on changing the course of our own personal life story. Wong explores this dilemma in 2046 by sometimes replaying the same scenario again but from different perspectives, such as having a flash forward to the future of Su Li-shen walking with a black dress during the film's earlier scene of Chow walking with Bai Ling after a dinner date with her. Wong does this to emphasize how Chow's relationship with Bai Ling is essentially a parallel reflection of his future relationship with Su Li-shen, which in itself is a mirror image of his brief affair with the Su Li-shen character from In the Mood for Love.

In essence, Wong is showing how we can never truly go back in time to change our lives because we are essentially repeating all our past behaviors and relationships throughout our lifetimes, just with seemingly different people. This goes with another Buddhist saying that each lifetime is essentially a repeat of our past lives-- we must experience the same scenarios and have the same relationships with people until we learn how to let go and enter the next stage of existence. At one point, Wong references Buddhism directly by ending his film In the Mood for Love at a Buddhist monastery, with Chow trying to let go of his past by whispering his secret love affair into a hole (the same hole which is referenced by the tunnel in the opening and ending scenes of 2046). By ending 2046 with an image of the tunnel fading to black, Wong is allowing all his characters to let go of their haunted pasts by whispering their secrets into this enigmatic symbol of salvation.

The most exhilarating moments of 2046 occur during the sequences set in the future of Chow's imaginary world from his writing. In these scenes, Wong explores the budding love a passenger on a train bound for 2046 (Takuya Kimura) develops for a hostess (Faye Wong) who can't reciprocate his feelings because she's a robot. This relationship parallels Chow's own relationship with Wang Jing-wen, the daughter of his landlord. The neon-lit colors of these scenes, along with their moody and operatic music and long, slow-motion panning shots, recall both Fallen Angels' futuristic scenery, and In the Mood for Love's mise en scene, but brought to a whole new genre of the science fiction film. The movements of Carina Lau as another robot hostess slowly tilting forward to reach for something on the train recalls the similar shot of the stewardess in Stanley Kubrick's 2001 reaching over to push a button in zero gravity on a spaceship. Science fiction elements, most notably with the use of futuristic, neon-like colors and Art Deco-inspired sets, have always infused some of Wong's previous films, so it's quite a delight to see Wong expand his toolbox by actually making a science fiction film sequence. Wong even dips into film noir in 2046 with Gong Li's "Black Spider" character, a dangerously alluring woman who always dresses in black and tempts Chow into a forbidden relationship like an archetypal femme fatalle.

As Wong's characters in 2046 brood and walk slowly through sometimes foreboding settings that imprison them, with even exterior scenes looking like they are closing them in, one recalls the similarly haunting film Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais. Like Resnais' film, 2046 envelopes his characters within their surroundings, which consist of enclosed, claustrophobic rooms, and long, mysterious hallways seemingly leading to nowhere. Also like Resnais' film, Wong's characters in 2046 are bound together and haunted by mysterious pasts, and are never fully to connect with each other despite their desire to do so. Both films portray the fragmented and multi-layered nature of time, as the past, present, and future continuously collapse into each other, entrapping their characters in an elusive labyrinth where the center is always beyond their grasps.

Similar to Resnais in Last Year at Marienbad, Wong uses his actors as sort of pantomimes to convey their interior states of mind; at one point, we even see Bai Ling with strings attached to her, as Wong tries to mold a popular Chinese actress to fit into his particular methodology of filmmaking. The way a character walks down a hallway, or up and down a flight of stairs, is just as important to Wong as the way they express themselves through dialogue. Like Resnais, what Wong is concerned with in 2046 and his other films is to have his actors' entire performances, from the way they move to the way they speak, convey a certain mood in a more subtle manner, rather than give traditional theatrical displays of obviously stated emotion. Although at times Gong Li, Zhang Ziyi, and Takuya Kimura give in to more melodramatic tendencies, Wong is able to for the most part fit them into his more subdued brand of acting that Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung have mastered already.

With its complex mise en scene and multiple layers of thematic elements, 2046 is Wong and Doyle working at the height of their powers. 2046 expands upon In the Mood for Love's more condensed narrative to tell a complex narrative which truly conveys the long and foreboding passage of time throughout one lifetime. While In the Mood for Love focuses on Chow's relationship with one woman, 2046 explores Chow's multiple affairs with various women, as well as his vibrant creative life by visualizing the science fiction narrative of his own novel. It will be interesting to see where Wong takes his artistic evolution next, as he needs to find a way to avoid the trap of repeating himself with each subsequent work. With The Grandmaster, a masterful mixture of traditional wu xia tropes with Wong's own distinctive voice, it's reassuring to see that Wong is expanding upon his previous filmmaking methods. Either way, as an artist, Wong has developed into a master of developing mood and tone through an almost purely visual and auditory level, and making films that explore what makes us most human-- the longing for an ethereal past that may forever be erased by an unknown future.

Wednesday, March 31, 2021

FILM REVIEW: ANTIPORNO

Beginning in the early 1970s, and lasting until the late 1980s, the Japanese film studio Nikkatsu released a series of sexploitation films known as Roman Pornos. As a result of the success of Nikkatsu's Roman Pornos, a whole new genre known as pink films emerged. These films mixed highly explicit depictions of sex and violence, with such provocative titles as Keep on Masturbating: Non-Stop Pleasure, Deep Throat in Tokyo, and Inflatable Sex Doll of the Wastelands. While some of these films strived to be films of genuine artistic merit, the majority of pink films existed solely to titillate audiences. Flash forward to 2016, and Nikkatsu rebooted its Roman Porno films with a series of new titles, and hired Sion Sono to create one of these films.

True to form, Sion Sono's entry in the new Roman Porno series is anything but a typical pornographic film. Sono boldly announces this intention with the title of the film itself--Antiporno (2016). Although it does have its share of nudity and explicit sexuality, Sono's film is actually an experimental commentary on the nature of fame, and also an exploration of the constantly evolving power dynamics between two actresses. As Antiporno begins, Sono sets us up to believe that we are watching a film about the domineering artist Kyoko (Ami Tomite) and her cruel manipulations of her put-upon assistant Noriko (Mariko Tsutsui). With its story of a celebrity's shifting relationship with her assistant, and its single location setting in the lead's house, Antiporno recalls Rainer Werner Fassbinder's The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant.

Like Fassbinder's film, the relationship between Antiporno's two female leads gradually transforms as Sono delves into the troubled past of his protagonists. A role reversal occurs between Kyoko and Noriko when Sono uncovers the true nature of their relationship with a clever plot twist that reveals the thin line between art and real life. Both Antiporno and The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant bathe the viewer in a luxurious color palette, with the former film being more like an Andy Warholish Pop Art burst of vivid colors, and the latter resembling a more subdued, classical Art Deco painting. Both films take place in a single location, but Sono is able to break through the confines of Antiporno's setting through vivid flashback tableaus, and dynamic displays of his two leads' constantly morphing power dynamics.

Ultimately, like Fassbinder's The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Sono is interested in exploring the sadomasochistic relationship between his female leads. Sono's protagonists are engaged in an eternal power struggle to reclaim control of their own lives, as well as redefining their roles with each other. Pleasure and pain, and being master and servant, are the dichotomous terms that tie Kyoko and Noriko to each other, and as the film progresses, their identifies merge into one. The concept of repetition and dualism is explored throughout Antiporno, both in the relationship between the two leads, as well as in the narrative structure of the film itself; Sono explores the same scenes over and over again through multiple angles, culminating in a dramatically explosive third act.

Like the majority of Sono's best films, Antiporno is a deconstruction of traditional genre tropes. While Nikkatsu hired him to make a porno film, Sono instead created a Fassbinder inspired art film about the nature of performance and celebrity. Like his previous film Why Don't You Play in Hell?, Antiporno uses the framing device of a work of art being created to explore the thin line between the creative life and the reality it reflects and distorts. Kyoke and Noriko are actresses, but the performances they create in the film within a film of Antiporno are a reflection of their sadomasochistic off-screen relationship.

This is what makes Antiporno and Sono himself so refreshing; he is constantly reinventing genre tropes to discover new ways of cinematic storytelling. Is Antiporno a pornographic film, or is it an homage to Fassbinder? Why can't it be both? Sono has always been interested in the subject of pornography throughout his career, most amusingly in his masterful Love Exposure, whose protagonist constantly struggles between feelings of guilt and his more primal lustful urges. In Antiporno, there is no guilt to hold back its protagonists, resulting a film filled with the liberating power of female sexuality. So, in the end, Antiporno is both a pornographic film in the traditional Nikkatsu Roman Porno genre, as well as a psychological, experimental exploration of sex as a form of power and control. Sono is removing the guilt usually associated with watching pornographic films, while also challenging viewers to view the depiction of sex in cinema as high art.

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

FILM REVIEW: JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH

In the 1960s, Jean-Luc Godard made a series of politically explosive films exploring how the tenants of Mao and Socialism informed the counter-cultural movement of the time period. This was best exemplified in his films La Chinoise, Sympathy for the Devil, and Weekend, which were both celebrations of the youth revolutionary movement of the time, as well as cautionary tales of the dangers of extreme radicalism. Shaka King's incendiary and powerful film Judas the Black Messiah (2021) continues Godard's tradition of exploring the youth revolutionary culture, but does it from the lens of modern day societal issues which mirrored the turbulent 1960s.

Judas and the Black Messiah, as the title implies, takes the Biblical tale of Judas Iscariot and his betrayal of the original revolutionary (Jesus Christ), and transposes it to the 1960s. The film is a tense exploration of the true story of William O'Neal (Lakeith Stanfield), a memer of the Black Panther party who also worked for the FBI as an informant on the party's actions. After infiltrating the Black Panthers, O'Neal rises up in the ranks to become a Security Captain, where he works closely to ensure the safety of Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), the chairman of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party. Judas and the Black Messiah explores the close relationship between Hampton and O'Neal, as well as O'Neal's partnership with Special Agent Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons), who works as his liasion with the FBI.

What makes Judas and the Black Messiah such a powerful film is the careful time King takes to develop the parallel relationships O'Neal has with both Hampton and Mitchell. King skillfully reveals how O'Neal is gradually drawn into the fight for racial and societal justice that Hampton and the Black Panthers stand for, while at the same time doing his part to bring down the party through his undercover work with Mitchell and the FBI. The central character of O'Neal is a morally conflicted figure, as he is working in tandem with the FBI to bring down the party which he most indentifies with as an African-American in the 1960s. It is this central schism of identity which provides much of the tension and power of the events that unfold in Judas and the Black Messiah.

Like Godard's political films from the French New Wave period, King couches his exploration of a revolutionary movement through a specific cinematic genre. Godard's counter-cultural films mixed genres like the musical, the gangster film, and documentary elements. Judas and the Black Messiah examines O'Neal's plight through the filter of film noirs from the 1950s, like The Maltese Falcon and The Big Heat. Like these films, King shows the corruption of law enforcement, and how his protagonist is both working for and fighting against these institutions. Much of Judas and the Black Messiah is filmed at night time in dark shadows, making it visually resemble a classic 1950s film noir as well. The opening interrogation scene itself, when O'Neal first meets Mitchell in a shadowy police station, is staged like something straight out of a Howard Hawks' crime film.

On an aesthetic level, King also films much of Judas and the Black Messiah with close-ups of his actor's faces, focusing quietly on their facial features and emotions. This recalls Godard's similar close-ups in films like Vivre sa vie and Masculin Feminin; like these films, King uses the camera to carefully capture and focus on naturalistic reactions from his actors, allowing them to give full-bodied, genuine performances.

In addition to his homage to classic noir films and The French New Wave, King also presents a three dimensional portrait of Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers that shows how they were driven by a genuine concern for societal and racial justice. While many associate the Black Panthers with being gun-totting, violent militants, King shows how the Panthers worked to improve and help out their communities, such as with their free lunch programs for inner-city youth, and their attempts to provide better education and access to resources for those in need.

As Hampton explains early in the film, the reason why the Black Panthers arm themselves with weapons is because they are essentially at war with a society that uses unjustified violence against those it wishes to oppress. King also shows how this oppression wasn't just against African-Americans, but against all races and subclasses within society. Eventually, Judas the Black Messiah shows how Hampton formed a Rainbow Coalition with both Latino and White people who wanted to fight back against systematic racism and subjugation. The enemy in this case was not only Capitalism (a common Godardian target), but the police force itself, which was responsible for the murder of so many innocent African-American lives. King also shows how the malevolent sway of the police extends well into higher echelons of government, all the way up to Hoover and the FBI.

And this brings Judas and the Black Messiah back to its central subject of law enforcement, and O'Neals complex relationship with this institution. Noir films were often about corrupt members of the police force, and King takes this cinematic trope and insightfully updates it to the plight of African-Americans in both the 1960s (the time period of Judas and the Black Messiah), and into the modern time period when police brutality targated at Black people is still prevalent. In this way, Judas and the Black Messiah's exploration of the eventual murder of Fred Hampton at the hands of the police in the 1960s is a dark mirror of similar recent events in American history, such as the murder of George Floyd and the countless other innocent African-Americans who are shot down by law enforcement every year. As King's profoundly unsettling film reveals, no matter how far our society claims to have advanced towards racial justice, we still have a long way to go.

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

FILM REVIEW: ZACK SNYDER'S JUSTICE LEAGUE

When one watches a Zack Snyder film, you have to know what to expect as a viewer. You're not going to be seeing an intense Martin Scorsese-like drama about sin and redemption, or a Godardian critique of capitalist society, Instead, as exemplified in previous Snyder films like Sucker Punch, Man of Steel, and 300, you're going to get lots of moody slow-motion scenes of characters brooding, accompanied by melodic rock ballads, violent, bloody action set pieces, lots of rain and sometimes snow, and a color palette that is oftentimes washed-out and grayish in tone. In other words, a Snyder film is primarily a visual and auditory visceral experience, rather than necessarily a film filled with themes and deep insights on society which you can write a graduate school thesis on. Snyder is an instinctual, visual artist whose films need to be felt and experienced to fully appreciate them, rather than trying to seek out complex, thematic layers of meaning. The new four hour version of Justice League is perhaps the ultimate example of a Snyder film, exhibiting all the faults and strengths of Snyder as a unique and compelling visual artist.

Based on the DC Comics series of the same name, Justice League (2021) focuses on the iconic superhero team of Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot), Superman (Henry Cavill), and Batman (Ben Affleck), as well as the lesser known but equally important characters of Cyborg (Ray Fisher), Flash (Ezra Miller), and Aquaman (Jason Momoa). Picking up right after Snyder's previous Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), Justice League opens up with Superman still deceased, and Batman going on a global quest to recruit teammates to take on and stop the nefarious Darkseid (Ray Porter), who is searching for three boxes of ancient origin which can destroy the world. Eventually, Batman is able to recruit the aforementioned superheroes, and the rest of Justice League deals with their efforts to seek out and destroy Darkseid.

I'm sure a comic book enthusiast can go into more details about the deeper thematic and plot dynamics of Justice League, but what makes the film interesting is Snyder's distinct visual stamp. Justice League is a big film with a capital B, from its marathon-like running time, to its labyrinthine cast of DC comics superheroes and villains, and mostly, its enduringly earnest and at times heart on its sleeve tone. Whatever critiques one may have about Snyder's films as being at times overly concerned with the visual aspects to the expense of subtext, one can't deny the genuine passion and heart that Snyder commits into all his projects, and Justice League is no exception.

With a massive four hour running time, Justice League seethes with Snyder's almost boyish sense of wonder and joy at his source material. This is best exemplified in an early scene where Flash rescues Iris West (Kiersey Clemons) as she is about to get hit by a truck. Snyder films this scene as one of his trademark slow-motion sequences, as we watch Flash leap through the air towards Iris, as hot dogs float all around them and the dream-like "Song to the Siren" plays in the background. For a brief moment, right before tragedy seems to be about to strike, we see Flash exchange a look of newfound love with Iris. This brief glance could only have been revealed through slow-motion, as it occurs during a rapidly out of control accident, and Snyder's combination of visual and auditory cues results in an almost transcendent moment of pure innocent beauty in the midst of chaos.

There are many other similarly blissful moments spread throughout Justice League, including another sequence with Flash near the climax as he makes one final, exhilarating sprint towards potentially saving the world, while remembering his promise to his father to redeem himself, as well as a montage sequence with Cyborg as he uses his powers to help out a struggling mother and child. Although it has its share of large action set pieces, all of which are expertly staged and stomach-churningly intense at times, it is these quieter moments of human connection that make Justice League more than just another generic superhero, blockbuster.

With a length of four hours, Snyder is able to flesh out the back stories of each of his protagonists in more detail than he could if he was confined to a traditional two, or even three hour, theatrical feature runtime. Snyder presents an almost encyclopedic collection of DC comics characters in Justice League by introducing many other heroes and villains throughout the film, including a mini-story arc for Atom (Kai Zheng) and brief appearances from the Martian Manhunter (Harry Lennix). The result is an epic, meta-mythological exploration (at one point, Snyder even introduces Zeus as a character) of the super hero genre as pop cultural ethos.

Martin Scorsese has rightfully criticized the glut of superhero films, many of which feel like carbon copies of each other, almost as if they were assembly-line products coming out of a factory. However, this new cut of Justice League feels like a much more personal and visually distinct project than other more generic comic book films. Although at times the constant flow of painterly-like compositions can be overwhelming and even exhausting, Snyder has crafted a film that is a genuine work of art, one where you can feel his passion and commitment in every single wildly creative frame.

Saturday, February 20, 2021

FILM REVIEW: NOMADLAND

Monday, February 15, 2021

FILM REVIEW: RED POST ON ESCHER STREET

Before he was a prolific and widely celebrated filmmaker, Sion Sono was a member of the avant-garde, public street performance art group Tokyo Gagaga, where he protested against all forms of authoritarian control. This rebellious spirit never completely left Sono when he began making films, and throughout his career he has experienced his fair share of artistic struggles against the conventions of the Japanese mainstream film industry. Although the majority of his films have been passion projects that fully displayed his singular voice as an artist, Sono has had to fight against producers who tried to streamline his vision. Sono explores this eternal conflict between art and commerce in his film Red Post on Escher Street (2020), resulting in one of his most personal and emotionally raw films.

With its kaleidoscopic and wide-ranging portrait of a vast array of characters involved in the making of a film, Red Post on Escher Street recalls the ensemble films of Robert Altman, but filtered through Sono's exuberant and wild worldview. As the film begins, Sono introduces his eclectic cast of characters who are auditioning for the lead roles in a new film by the fictional film director Tadashi Kobayashi (Tatsuhiro Yamaoka). Kobayashi opens the casting call for his film to amateur performers, and Sono delves into the backstory of each of the apiring actors who attend the audition. Things get complicated in Red Post on Escher Street after Kobayashi finally chooses the lead actresses for his film in the form of Yasuko Yabuki and Kiroko, but his producer forces him to replace them with popular and physically attractive, but less talented actresses.

It is interesting to note that the actors themselves in Red Post on Escher Street are also non-professional thespians participating in an acting workshop. Sono shot the entirety of the film in only eight days as a training exercise for his actors, and he is able to elicit naturalistic performances from them. In fact, some of the performances are more authentic and heartfelt than the work of more established professional actors.

It is this turning point in the film that reveals the ultimate theme of Red Post on Escher Street-- the desire for artistic freedom in a world dominated by conformity to mainstream edicts. The last act of the film, as Kobayashi begins to unravel while he struggles to film his project with his unwanted leads, contains some of Sono's most breathtakingly liberating cinema. The film set itself becomes a microcosm of the wider society at large, as Kobayashi is forced by those above him to focus on the bland actresses in front of him, while he is more interested in the less outwardly appealing, but unqiue extras at the margins of his camera's frame. While the film shoot descends into frenzied chaos, it is within this anarchic environment that Kobayashi is able to finally unleash his long repressed yearning for complete and total liberation as an artist.

Red Post on Escher Street culminates with the protagonist running away from authoritarian control and towards what he perceives to be a symbol of his freedom. Love Exposure, Himizu, and Why Don't You Play In Hell? all culminated in a similar scene of the lead rapidly sprinting away from authority and towards an unknown future, but Red Post on Escher Street is Sono's first film which shows the protagonist actually running back to that which he was escaping from, and finally asserting his control over his oppressors. Perhaps after all these years of struggling to maintain control over his art, Sono has finally regained the passion which he has longed for throughout his career with the making of Red Post on Escher Street.

Indeed, Sono films Red Post on Escher Street with an almost newfound sense of freedom, as each frame feels as loose and energetic as some of Sono's earlier, equally liberating films like Love Exposure, Strange Circus, and Guilty of Romance. Unlike those films, however, Red Post on Escher Street is almost completely devoid of any sense of nihilism and despair. Instead, for the first time Sono embues his work with a comforting mood of ebullience. There is still a hint of darkness with the troubling incest theme of Yasuko's story, and the suggestion that she may be homicidal, but overall Red Post on Escher Street is a surprisingly optimistic story about celebrating the power of those at the margins of society.

While the literal meaning of the film's title refers to an actual red mailbox located at Escher Street where the actresses mail off their audition applications, Sono is also alluding to the graphic artist M.C. Escher with the constantly intertwining narrative of Red Post on Escher Street. Like Escher's portraits of asymmetrical objects that are continuously merging and receding from each other, Sono intricately interweaves his multiple narratives by going backwards and forwards in time, and replaying certain scenes to view them from alternate perspectives. This is a method which Sono has employed before, most noteably in Love Exposure, and it is a way for Sono to further deconstruct and find ways to break apart traditional narrative structure in innovative ways. It's always refreshing when an artist such as Sono is able to find his voice again after struggling for years with more mainstream projects, and Red Post on Escher Street is one of Sono's most artistically accomplished and exhilarating works in years.